Sundance Film Festival 2019: Native Son

By Andrea Thompson

It makes just as much sense for the film “Native Son” to take place on Chicago's South Side now as it did in 1940 when the book it was based on was published. Perhaps even more, since Chicago has become the setting to explore issues involving race and violence, some sensitively and others less so.

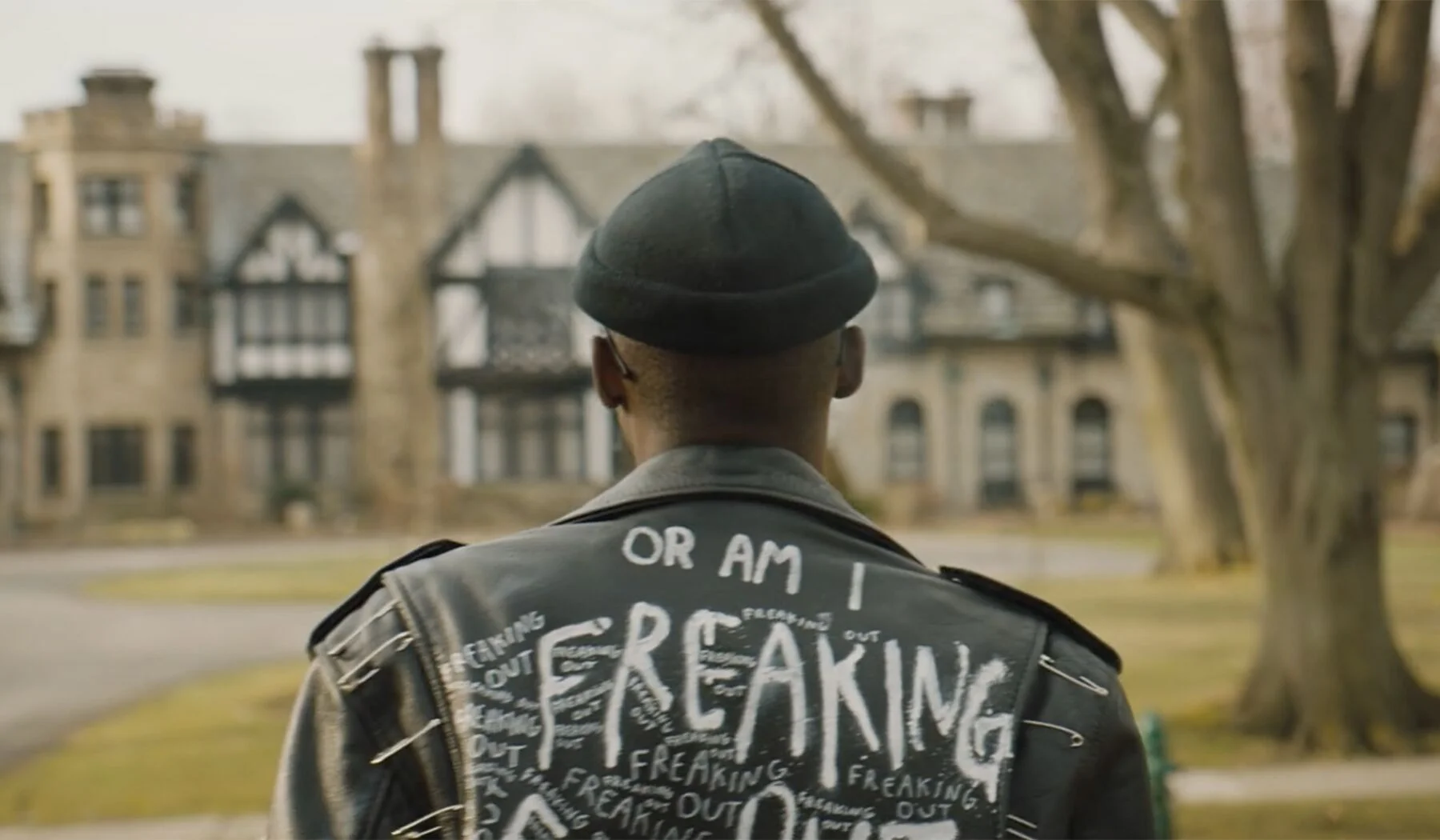

Once the film establishes the sights of the Chicago skyline, it begins much the same way the book does, with Bigger Thomas (Ashton Sanders, the teenage Chiron in “Moonlight”) killing a rat in his family's apartment. What he and his family (still) struggle with may be familiar, but Bigger is all modern, or rather, 80s nostalgia run fashionably rampant, with his punk aesthetic and green hair.

He's also both perceptive and, as he himself later notes, blind. He refuses to get involved in the more dangerous, illegal activities those around him partake in, such as drug dealing and robbery. He does get a chance when he's offered a job as chauffeur to the Daltons, a wealthy white family. From the first, his interactions with them are fodder for the kind of humor the family remains oblivious to, from the family patriarch to his blind wife, and how Bigger reacts to their attempts at kindness will shape his fate.

However, it's the daughter Mary Dalton (Margaret Qualley) who may represent a threat to the fragile stability Bigger manages to find in the Dalton home. Margaret is the kind of well-meaning child of privilege who is dangerously oblivious to that privilege, making her political activism and her attempts to befriend Bigger and his girlfriend Bessie (Kiki Layne of “If Beale Street Could Talk”) not only fall flat, but incur disastrous consequences.

How those consequences play themselves out is where the movie fizzles, especially in how it ironically blames Mary far more for them rather than her parents, who turn out to have financial interests in the forces keeping Bigger in poverty. A certain amount of softening is inevitable. Novelist Richard Wright pulled no punches in how he depicted Bigger Thomas as a failed human being in every sense, unable to connect or understand himself, let alone others. Such a monstrous human being would not only be difficult to sympathize with, they could risk becoming a racist caricature, which was also an accusation Wright had to contend with. Wright himself made no excuses or apologies for Bigger's actions, he only tried to show how every now and then that such a racist, dehumanizing system would naturally spit out someone like Bigger.

It's hard to go to that place, and it's understandable why director Rashid Johnson, a visual artist and Chicago native who's making his feature film directorial debut, and screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks, the first black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for drama, cannot bring themselves to fully bring the horror of what Bigger becomes to the screen. Johnson and Parks are able to make him much more than a stereotype, with his love of rock and classical rather than hip hop, and especially how he interacts with his environment. Chicago may be a common setting, but few movies do the city justice, either depicting it as a wasteland of violence or a stand-in for any metropolitan area. Not so here, as Johnson's skillful direction gives us a sense of not just the vastly different neighborhoods, but experiences Chicago has to offer.

The only thing missing from this critically loving depiction is also what's holding the film back, and that's what we're all capable of, from a single brutalized person, to a city, or even a country. In the book, the system comes down on Bigger in a fashion that makes death look like a kindness, grinding him up in the slow, sadistic process inherent in a legal system intent on making an example and quickly forgetting what it has wrought. To create the same sense of drama, “Native Son” instead uses symbols so obvious that Bigger has an actual target on the back of his jacket when he goes on the run. It's understandable why the filmmakers wanted to avoid the worst of what we are capable of when the evidence of it has been so painfully obvious than ever over the past few years, but it also makes the story become something far more common, and thus less than Wright's vision.

Grade: B-