Memory Informs Trauma in the Extraordinary Documentary 'One Child Nation'

By Andrea Thompson

Growing up, I would hear about families adopting girls from China in nothing but the most positive terms. Why not? Everyone knew about the country's policy, which encouraged families to limit the number of children they produced to one. Combine that with a widely shared preferences for sons, and it became common practice for families to give up their daughters. So when couples were looking to adopt, it seemed like a win for everyone. Girls got to go to loving homes they wouldn't otherwise have, and those who wanted to experience parenthood could do so in an easier, effective process.

The documentary “One Child Nation” depicts a truth that is not only more complicated, but more horrific than many could have imagined. Director Nanfu Wang grew up in China herself and thought little about the propaganda that was everywhere when she was a child, extolling the joys of having a single child and threatening punishment for those who violated the rules. She so absorbed the messages, she recalled being embarrassed she had a younger brother.

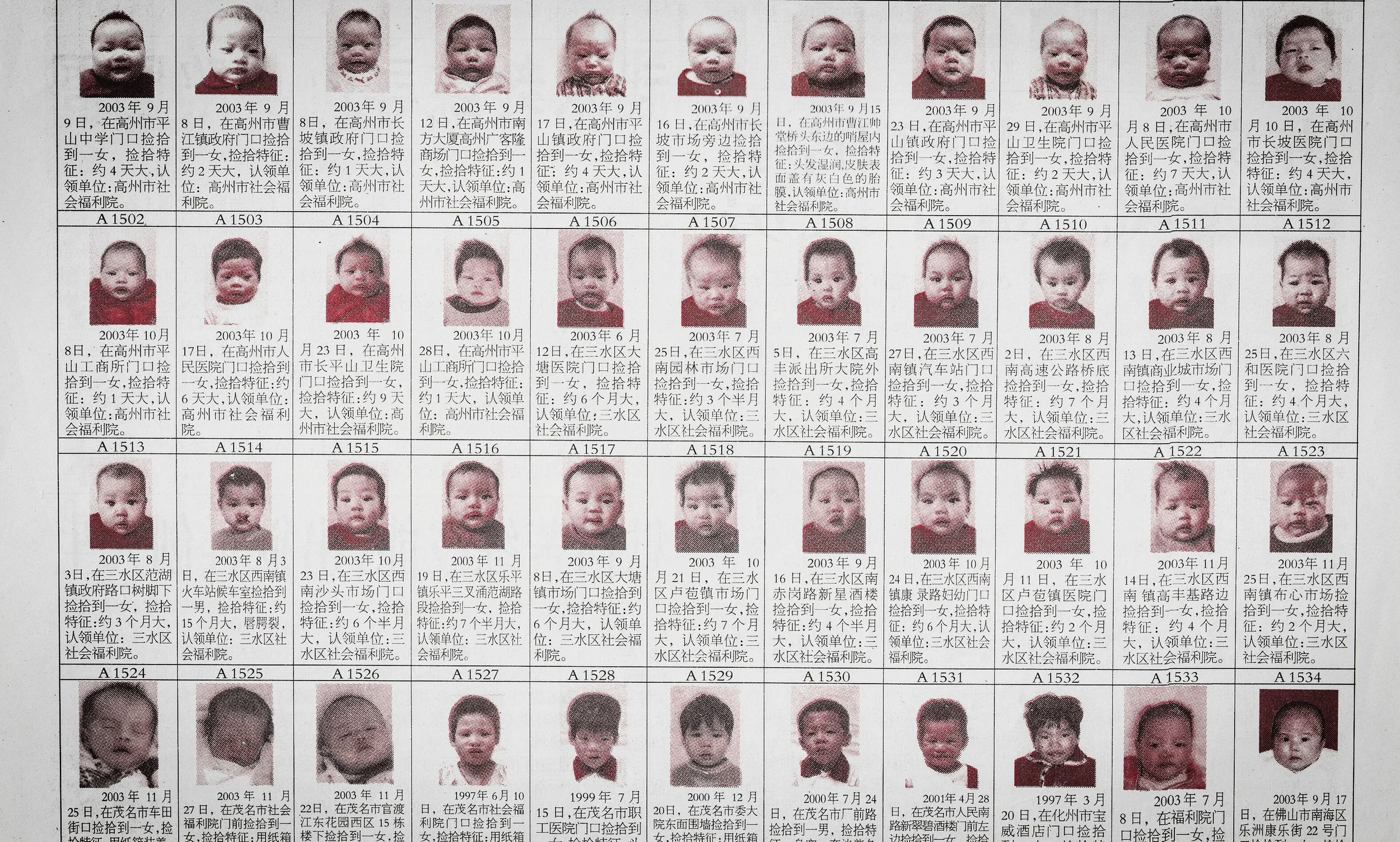

Then Nanfu became a mother herself, and decided to speak with everyone from government officials, neighbors, and her own family about the effects of the law China upheld at all costs. What she discovered shocked and disturbed her, from her own brother, who knew that if he'd been born female he would've been abandoned, to the government officials who performed forced abortions, to the traffickers who provided girls to orphanages for couples to adopt, and other families who saw their daughters literally ripped from their arms, to be later taken in by American couples who were tragically unaware they were abetting kidnapping.

One of the most painful stories is of the women who were abducted for forced sterilization and abortions. As one government worker recalled, some of the women had managed to keep their pregnancies hidden for quite some time, and were eight or nine months along when she terminated their pregnancies. She justifies it by saying they were waging a population war and that she'd do it again, but at least one village midwife doesn't pretend she wasn't aware she was harming people, and has since attempted to atone by assisting infertile couples.

Yet the stories are hardly less harrowing once orphanages realized there was a market for international adoption. Rather, the violence becomes more emotional rather than physical. It's hard to feel sympathy for those who use children as currency, yet the family who was prosecuted for being the largest traffickers in the country described how they and others at the bottom of the social rung were initially trying to save the many abandoned girls they would routinely come across. As Wang's own mother described helping her brother abandon an infant girl who then died a very painful death in the village market, it's hard to doubt claims that many of the babies they gave to orphanages most likely would have perished.

However, some weren't so willing to give up their children, recalling how officials came to their homes and took children away, falsifying their stories later. Twins separated at birth seemed to have become heartbreakingly common, with many adoptees preferring to remain ignorant about the origins of their typically more well-off lives which are often a stark contrast to their impoverished birth families. Shockingly, they are often the only ones who don't express their approval for the one child program; it is Wang and the generation after who generally decry it. Everyone else, from Wang's relatives to the officials, both regretful and not, approve of the policy and maintain their lack of culpability, repeating one phrase so often it began to feel like an echo across the country: I had no choice.

Amazon Studios

Recalling her own childhood and how she unthinkingly embraced state propaganda as well, Wang mused, “When every major life decision is made for you, it's hard to feel responsible for the consequences.” Such a refusal to take responsibility will continue to have ramifications, as China is even now in the process of not only revising its policy for a two child one, it's erasing all evidence of the former and its history. In such an environment, it's not the stories that disturb most. It's the silence that lies in an utter quiet which insists everything is fine and refuses to acknowledge dark truths hiding in plain sight in a kind of mass, willful blindness. 85 minutes is a relatively short time to bring such a wide range of stories to light, but it can't be said that “One Child Nation” doesn't make the most out of what it chooses to focus on.

Grade: A-